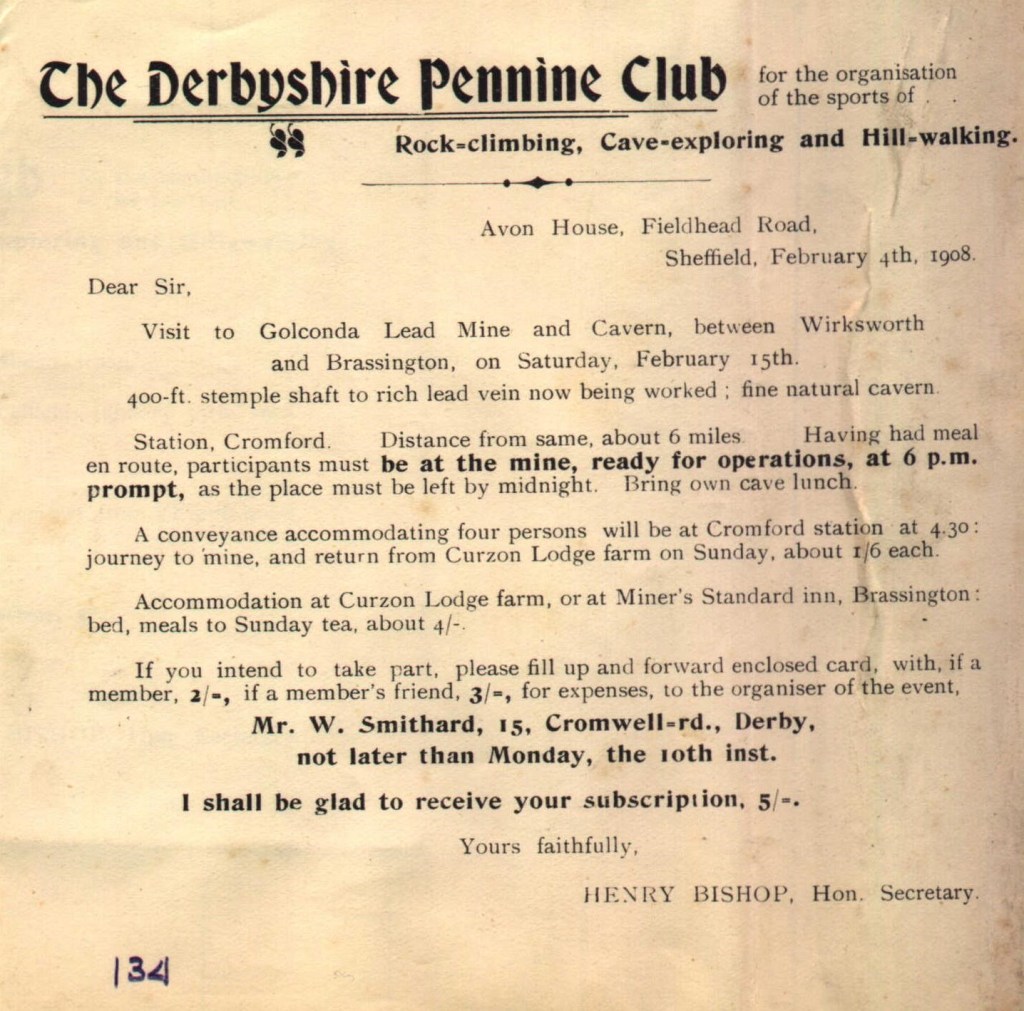

15th February 1908

By W. Smithard:

The Golconda Lead Mine, near Wirksworth, with its 350 feet of stemple shaft and fine natural cavern, was visited on February 15th 1908. “Yo sweeten,” drawled old John Bacon, as he gazed at the perspiration streaming down our visages. And we did. But we had not heard ‘sweat’ pronounced ‘sweet’ before.

We were in the depths of the Golconda Lead Mine, and John had been piloting us briskly through a maze of old workings – low tunnels, where we had mostly to maintain a stooping posture, and sometimes to do a crawl.

The Golconda is not one of those spent, or laggard, mineral veins that have been ‘nicked’ during the recent rise in the price of lead. It has been worked continuously for a hundred and fifty years, and mostly by the Bacon family. There was a steady output of galena from the Golconda before and during the boom, and its jog-trot continues now that the price has fallen so heavily.

The outworks of the Golconda are neither modern nor elaborate. In fact, the appliances are delightfully primitive and picturesque. There is a noble winding drum, composed of timber, and fixed horizontally. It is occasionally worked by horsepower for hauling the lead ore out of the mine. The dignity and repose of this fixture make a powerful protest against the vain glories of hustling.

After the slow and serene movements of the stately drum-major, the jerky activities of the jigging machine seem quite frivolous, though they would be most funereal if contrasted with the furious revolutions of an old fashioned mangle.

The jigging machine consists of a rectangular wooden tank, in which an iron sieve is moved up and down by means of a lever, in the form of a ponderous plank, actuated by hand power.

Here, to use homely metaphors, the wheat and the tares are plunged together into a cold bath. The waters are troubled, and the sheep are thus rigorously separated from the goats. As though by magic, the black-sheepish fragments of galena arrange themselves as a compact bottom layer in the sieve, untainted by any speck from the giddier-goatish barytes, which close their ranks in an equally exclusive upper stratum.

In this cool way comes about the final parting, after ages of close companionship. The first rift in an eternity of rest comes when the delving miner insidiously fuses a dynamite cartridge, which he has placed in the bosom of the vein.

No longer capable of complete solidarity, galena and barium sulphate still cling to each other in the individual lumps and fragments that result from the explosion. Tumbled into small iron wagons, sheep and goats, wheat and tares, still very much intermingled, have a tram ride to the foot of the fifty-fathom shaft. Then the drum major revolves, and the spoils of the mine are brought to the light of day.

The process of disintegration is furthered by the use of sledge hammers, and completed by a simple crushing machine, with a hopper, iron rollers, and a fly-wheel, actuated by hand power.

Then follows the ordeal by jigging machine, after which the ore is fit to be measured before being passed on to the smelting furnace, while the caulk is put aside for use in the manufacture of paint, and for sundry other purposes.

When we arrived at the Golconda, the owner and his colleagues were seated round a bucket fire, taking a snack in the ‘coe,’ as they call the shed in which they keep their implements, and store the dressed galena.

The miners have a vocabulary of their own, and they use many words that are foreign to persons not connected with their ancient craft.

The snack disposed of, we, Archer, Puttrell, Rains, Smithard, and Winder, accompanied by our right trusty mining friends, Sheldon and the Bacons, got us into the fifty-fathom shaft, and effected an easy descent by means of the stemples, or wooden bars, fixed horizontally therein. The shaft is sunk through magnesian limestone, locally called dunstone, which forms the roof of the vein, the sole consisting of mountain limestone.

The vein is in the form known as a ‘pipe,’ i.e., the ore is bedded horizontally or nearly so. Connected with the pipe are ‘rakes,’ feeders, and scrins.

Having made us ‘sweet’ in the workings, John Bacon took us down other shafts to a level some four hundred feet below the surface. Thence we clambered up steep slopes of rock and over great spoil heaps to the Golconda cavern, a huge place which has been formed by a great fall of rock from the roof of the mineral vein. The cavern is very symmetrical, and the sides slope towards each other, meeting in a narrow roof which is cleft from end to end. The floor consists of immense blocks of limestone, with flat surfaces and clean fractures, piled at all angles, and separated by deep fissures. Lit up with magnesium ribbon, the northern end of the cavern is a magnificent sight. Between two great crags is a wide and deep recess, into which water is always splashing from the lofty roof. Here numerous rocks are piled pell-mell, and they are covered with pure white stalagmite of beautiful forms. Crystal pools in the hollows contain many of these little balls of calcite, known as cave pearls. There was but one drawback, if any, to our intense enjoyment of this splendid scene. It was the thought of that fifty-fathom shaft up which we had to climb before we could have supper. We were ‘sweating’ more than ever by the time we reached the top.

By F. A. Winder. From his unpublished and undated manuscript titled ‘A Wanderer in the King’s Fields’:

Mention has already been made regarding the misleading habit of old miners regarding the assumption of a depth of forty fathoms to every ancient engine shaft, but such an estimate would be incorrect in connection with the Golconda Mine. In this case the Main Engine or Drawing Shaft is approximately 460 feet in depth and the estimate appears to be grossly underestimated when a visitor is making an ascent to the surface.

The mine is reported to be one of the most ancient in the King’s Field, and it is also distinguished by the peculiar formation of the shaft. Those sunk by Saxon labour were generally oval in shape, and shafts sunk a later date were round, oblong or square, and the writer has made acquaintance with the idiosyncrasies of them all.

The Golconda is nearly unique in character, for it has been sunk in the shape of a pear; a wood partition dividing it into two separate compartments, the larger of which is used as the Engine or Drawing Shaft, and the remaining three cornered cavity utilized by the miners when descending to, and ascending from the workings. The writer is in a position to describe these original features, for he had ample opportunities to become acquainted with them during his first visit to the mine.

It was an official meet in the early days of the Club, and the Sheffield contingent consisted of three hardened cave men and the writer, who was then in a semi noviate stage. Another party from Derby was to make contact on the site. Unfortunately, the train from Sheffield, which was scheduled to stop at Cromford, started on time and in consequence the party, who had relied on its usual tardiness, only caught a brief glimpse of the guard’s van receding from the platform.

The next train was an express one to Matlock, and on arrival, it was necessary to hire a trap. Motors were then unknown. The result of the delay was that the Derby attachment arrived first, and waxing impatient, descended the shaft under the guidance of the captain of the mine.

Two miners had been left at the surface to act as guides for the stragglers, and after changing our clothes in the ‘coe,’ we crossed the yard to the pit head and, entering a tiny cabin and descending a short ladder, found ourselves at the top of the climbing shaft.

This, as has been previously mentioned, was triangular in shape, the base being formed of a wooden partition, a series of stemples holding the worm eaten boards in place. The timber was certainly ancient, for on several occasions during the descent, the writer pushed a foot through the boards into the thin air of the main shaft.

One of the professionals had the misfortune to own a ‘peg-leg,’ his foot having been amputated below the knee. This disability did not, however, prevent him from manipulating the stemples, for the village shoemaker, assisted by the local carpenter and helped by the neighbouring blacksmith, had evolved a shoe for the peg on the lines of a river driver’s boat, with long spikes in the sole. It answered its purpose admirably, but one of the man’s mates warned the writer not to stand next to the crippled one, if they should meet later at the bar of the village pub. “Tom’s excitable,” he explained, “after his second pint, and its painful if he treads on your toe with that spiked boot of his!”

The climbing shaft at the Golconda has one peculiar feature, as compared with others in the district, namely being formed in one straight line instead of a series of shorter climbs separated by levels or horizontal drifts. The shaft is therefore provided with trapdoors every 60 feet to limit the depth of a fall, and also to guard against a pick hammer or crowbar falling the full depth, and thereby acquiring momentum. The miners usually stuck such implements in their belts, to leave the hands free, and a sudden jolt was liable to dislodge them.

On the occasion now being described, the skipper had, through mistaken kindness, left the doors open to facilitate the descent. One local aspirant for glory looked down the shaft and saw what he thought to be a candle burning at the bottom. The explanation that the supposed candle was really a large flare lamp, gave him such a distorted impression of the depth, that he became violently ill in his interior anatomy and he was left, sitting forlornly in front of the fire in the coe.

The rest of the party entered the shaft and made their way downward. The procedure of negotiating stemples is not difficult once the knack is learnt, but the man above the writer gave him sound advice. “If I happen to tread on your fingers lad,” he explained, “say ‘nowt’ as, if you call out, I may keep my boot on you ‘till I know what’s wrong. If you stay quiet, I shall shift my foot next step.” The man was correct. His foot did encounter the writer’s fingers, who remembered his instructions, kept still, and escaped with bruised, not broken fingers.

Eventually the bottom of the shaft was reached, from which a short passage brought the party to a ladder leading to the floor of a small artificial chamber from which the main shaft was again reached. Here an iron ladder spiked to the wall enables a miner or visitor to negotiate the remaining depth to the old and original wagon gate, the iron rails on the floor being 460 feet below the surface. (This depth has not been checked but is believed to be correct).

It would be impossible, within the space of a short article, to describe the ramifications of the mine. ‘The galleries appear to be endless, and it would probably be no exaggeration to say that a complete survey would show several miles of workings. Such a survey would, however, be impossible owing to the total or partial collapse of a great number of the headings.

Therefore the members of our party contented themselves with a walk to the face, where the vein was actually being worked, and a brief inspection of the natural caverns at the far end of the mine. The route is complicated and involves an awkward traverse round a bulging rock, similar in character to the ‘Nose’ or The Pillar Rock, and the ascent of a 30 feet sump. The latter is not stempled, but is provided with climbing stones, or notches let into the sides of the shaft. (There is a similar shaft in Pindale, near Castleton, where it is possible to climb over 100 feet without the aid of a rope!). These, at the time of the visit, were still in good order, though probably 200 years old, and the ascent could not be classed as difficult.

The principal cavern is reached through a labyrinth of loose rocks, and consists of a large natural tunnel with an inclined roof and a curious slabby floor. At the far end is the feature of the cave, consisting of a natural grotto ornamented with calcite and with a petrifying shower from the roof. The water is impregnated with lime, and any article left exposed to its action, speedily becomes coated with a layer of stalagmite. On the occasion of his visit, the writer picked up a fragment of an oak stemple encased in a layer of the deposit nearly an eighth of an inch in thickness. The grotto is also a good place in which to discover cave pearls, and the writer still remembers the patter of the rain on the oilskin coat of one of the party whilst he grubbed for pearls beneath the fall.

Having heard of the peculiar properties of the water, the writer had provided himself with a toy composition mouse, which he deposited in the water, and that mouse later got him into trouble. He retrieved it after a lapse of four years, and finding it covered with a layer of white sugary deposit, took it home and placed it in a tray with other geological specimens. The collection was unfortunately discovered by a small relative, who thinking the mouse a spice one, endeavoured to bite it in half, and in consequence, two of his front teeth came to grief! The writer was not worried. The mouse was not injured and the teeth, being of the milk variety, would he knew be replaced by nature in due course. The loving mother of the boy took another view of the matter, and was most indignant regarding the cruel joke played upon her offspring! When the writer mildly suggested that the mishap might be regarded as a judgement for attempted theft, his argument only served as a further incentive to heap coals of fire upon his head. That however, was still to come.

One other feature of the cavern remained to be examined, namely the ‘Pulpit Rock.’ This is an outstanding block of limestone bearing a strange resemblance to the variety of pulpit found in a church, and formed a suitable background for the inevitable photographic group.

On the return journey, the writer remarked on the particular shape of some timber casing shoring up a fall. He was informed that the casing was formed of the backs of pews taken from Wirksworth church, the wish having being executed in the dim past when the requirements of the ‘Old Man’ ranked even prior in some ways to the preservation of the edifice. When the informant was asked what the incumbent had thought about the procedure he replied, “Parson did not mind. He wanted his dishes of ore from the mine.”