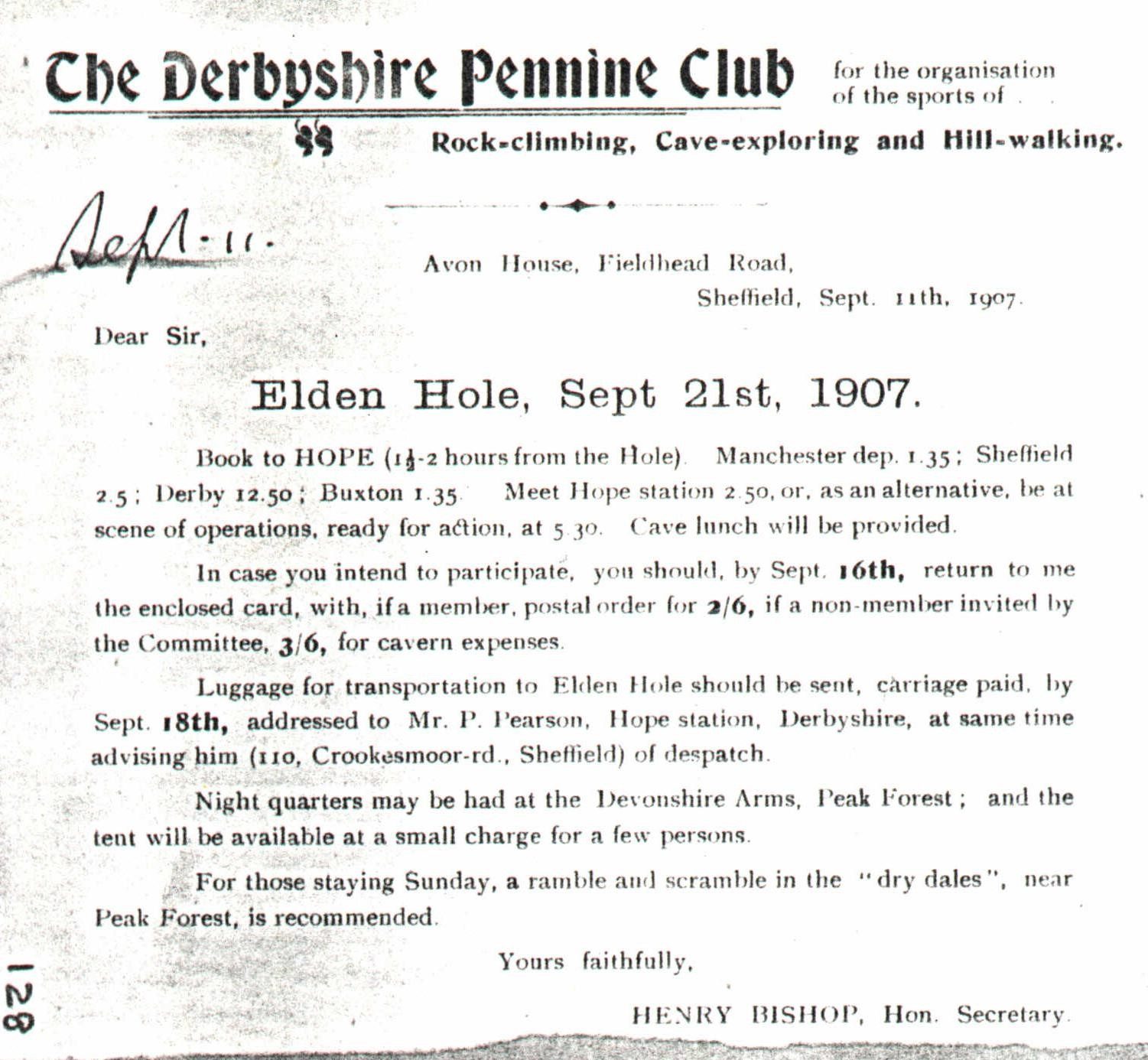

21st September 1907

By H. Bishop

On September 21st a most interesting meet took place at Elden Hole, near Peak Forest. Fourteen or fifteen men were lowered down the shaft, which is almost 200 feet in depth. Descending the steep scree slope at its foot, and passing underneath a low part of the roof, operations were commenced at one corner of the large chamber, where the presence of a swallet was suspected. It was not possible to make much progress here, so another spot somewhat higher up the scree was tried. The removal of a few large stones disclosed a downward slope; and continued removal work allowed of a depth of 70 feet being attained. There are still possibilities here.

By W. M Sissons

I descended the above on September 21 1907 with the Derbyshire Pennine Club. Operations started at 3.30 and 20 turned up. The ‘Bosuns Chair’ was the descent chosen and a telephone was fitted so as to keep in touch with persons down below. I descended at 9pm.

It was very misty when I reached the 160 feet level. There were seven on the rope to lower one. A 70 feet gradual slope from the 180 feet level led into a very large chamber. A splendid arch spans this chamber and the walls were covered with huge stalactites a good height up. We traced an old watercourse by removing a lot of stones and got 60 feet down but came to a blank. The telephone was very useful but got smashed in descending and was patched up.

It was a very wild night when we arrived back at the top. A good fire was kindled so had “summat hot.” One man had a narrow escape. A big stone grazed his head when he was being hauled up. The stone had dropped 100 feet when it grazed him. I walked back to Bradwell over the tops with Amies and Smith. All three of us were dead tired and arrived back at 4.15 early Sunday morning. Smith, though in costume, did not descend. Hauled at ropes all night (so he says).

By F. A. Winder

It was in 1907 that the writer made his first acquaintance with the hole; and though thirty years have passed, and he has repeated the experience several times since that eventful night, it is still to him a most vivid memory.

The Meet was arranged by the Committee of the Derbyshire Pennine Club, and was on a large scale. Many of those present have, (alas!) taken a longer journey from which there is no return.

The occasion was the writer’s first experience of deep cavern work and, as a matter of fact, it was one of the tests imposed upon him regarding suitability for membership. It is to be feared that, if some of the London Institutions were as careful in selecting their members, there would be many empty chairs, for, to a novice, the test was severe.

Incidentally, the date had been fixed some weeks in advance, and, during the interim, the conversation of the writer’s fellow-members did not tend to raise his spirits, for the tales recounted by pot-holers can only be compared to the experiences of fishermen, so far as exaggeration is concerned.

‘The Hole’ was made out to be a most fearsome place, and, though some of the incidents were undoubtedly true, they were presented to him in a most lurid form. He heard accounts of men saved as it was by a miracle – and the lifeline, of falling stones, and rope ladders of fearsome length.

The subject was revived during the walk over ‘The Tops’ to Eldon Hill, and to put the matter plainly, he became so nervous that nothing would have given him greater pleasure than, later, to see the ladders, together with a selection of his tormentors, vanish with a rush down the Hole.

On his arrival at the scene of operations he found quite a congregation gathered round the objective. Some of the members had travelled via Peak Forest, others over the hills from Bradwell, and a learned Professor, who represented the geological section of a famous University, gazed about him in an absent minded manner. He was short in stature, round in face and his eyes were partially obscured by the largest size in spectacles.

G.H.Harrison had temporarily forsaken his duties as permanent adviser to perennial Lord Mayors, and Puttrell, in his capacity of leader, was evidently taking his duties very seriously.

In addition to the members of the Club, there were other guests in addition to the Professor; and a triumvirate of three, who represented the Yorkshire Speleological Association, evidently held the Hole in little awe despite its ancient history.

On looking back, after a lapse of many years, the writer will still disagree with the attitude taken by those northern visitors in respect of the Derbyshire caves. It is true that the vertical ‘Pots’ of the Ingleborough district are deeper than those of the Peak, with the exception of Oxlow Cavern, but it is doubtful whether their exploration entails as much risk as the combination of mines and caverns found in the Derbyshire district.

There are few more disagreeable experiences than descending a ladder three hundred feet in length down a shaft, which shows indications of collapse, and some of the ancient levels have to be treated with respect.

Eldon Hole is, however, a comparatively harmless place, provided that the gear is sound and has been rigged by competent hands. The method chosen on the occasion now being referred to was a bo’sun’s chair attached to the end of a strong and lengthy cable. This, to a novice, appeared sufficiently enthralling, but there were additional complications owing to the chair having to be pulled over the centre of the Hole by another rope.

As the writer was tied into the chair his teeth chattered like castanets, and an attendant slipped something into his mouth. “Bite on that,” he said, kindly, “it will stop the noise.” It did, for the gag was a tallow candle, and the state of his nerves will be realised when it is mentioned that he did not recognise the taste, and was still chewing the fat with contentment when he arrived at the bottom of the rift.

The dimensions have been given in many books, but to save the reader the trouble of reference, it may be stated that the top of the vertical portion is shaped like a gigantic wedge over a hundred feet in length, and a central width of thirty feet.

The size rapidly decreases, and at a depth of sixty feet from the surface it measures only sixty by by fifteen feet. Then it again widens out into a typical cave.

The floor of the chasm, which is really an anteroom to the main chamber, slopes to the south, and is composed of hundreds of tons of boulders and smaller stones thrown down by tourists in order to hear the noise as the missile rebounds from wall to wall, and finally breaks to pieces on the floor.

It may be mentioned that, at one period, the life of the stone wall, which protected the cavity, was estimated to be seven years, and annual attention was required to make good the effects of wastage.

A wire fence now surrounds the hole; and, as the strands are useless for sounding purposes, the fence has remained intact.

There is a tale told of one absent-minded professor, who wished to estimate the depth by timing the fall of a stone. He took a fragment of rock in one hand, held his gold watch in the other, and then threw the timepiece into the rift. His remarks incidental to the error are known, but cannot well be repeated.

As the writer landed at the point where the watch must have fallen, he heard a yell of warning from above. It was due to the action of an onlooker who had leant against the wall, which had collapsed and started a stone avalanche.

Fortunately, the rope was slack, and he rushed for cover with the chair still strapped to his trousers.

The incident was useful training for his later experiences in France.

The floor of the outer cavern is formed like a shallow inclined gully, the lower part of which passes through a natural arching in the rock about four feet in height; and, on passing through this portal, he obtained his first view of the main chamber. It appeared very similar in form and size to Lord Mulgrave’s Dining-room in the Blue John Cavern, except that the roof was a dome, and the floor sloping and boulder-strewn.

There are still traces of stalagmitic formation on the roof and sides, but these could not be seen, as the interior of the cavern was obscured by smoke from flare-lamps, candles and the ignition of magnesium powder.

On looking round for the remainder of the party he observed Sprules and Puttrell near the right-hand wall, and they were behaving in a similar manner to excited terriers at a rabbit burrow. They had presumably discovered a new passage of which they were endeavouring to open out the entrance.

He was at once pressed into service, and an hour’s work cleared the orifice of surplus stones.

It was a typical Derbyshire swallet, waterworn and floored with rounded limestone boulders. They lay at the angle of rest; and, as each stone was removed, two of its adjacent fellows rolled down to take its place.

Then Bishop appeared at the opening, and his mournful face showed that he was having a happy time. He is always that way in a cave.

There were now sufficient workers to form a chain. The boulders were passed from hand to hand, and a way opened for a distance of sixty feet.

Sprules was in the lead, and as he was endeavouring to pick up a particularly elusive pebble, it slipped from his fingers through a chink in the floor. It proceeded downwards with a series of bumps culminating with a squash as it hit some soft resistance.

More stones followed the first one, and then someone suggested that as Sprules was evidently sitting on the top of a hole possessing unknown depth it might be advisable to secure him safely with a rope.

The suggestion was approved, and then a few minutes’ work with a crowbar revealed the entrance to a narrow and vertical cleft, evidently a natural swallet.

Sprules, after removing his superfluous apparel, for the route was extremely restricted, forced himself through the chink and wended his way downwards. The writer followed him, steadied by Puttrell from the top with the rope.

The cleft was a delightful place, affording a little rock climb of about thirty feet, just a typical Cumberland gully transferred, as though by a magic wand, into a Derbyshire cave. Even chock-stones were in evidence, wedged between the faces of the living rock.

At the foot of the lowest pitch was a beach of amber-coloured sand, water-washed and evidently blinding the natural overflow of the ‘sink.’

Further progress was impossible, as every particle of excavated material would have had to be transported to the higher levels through the eyehole and up the slope of unstable boulders.

This fact was practically demonstrated, for suddenly a kind and learned face looked down from above, and a gentle voice murmured, “May I too come down?” Simultaneously with the words a rounded stone of the size of a Belisha Beacon shot through the opening, followed by a heavy and nailed boot – the Professor had slipped.

He stuck, but the stone gathered momentum and travelled down the cleft with the velocity of an old-fashioned cannon ball.

The writer, in a state of absolute terror, watched it fall and counted the number of times it bounced from wall to wall, and as he reached nine a plop indicated that the thunderbolt had landed on the only bit of sand unoccupied by a human form.

The Professor, who was the culprit, was forgiven. He was so gentle and apologetic, and later the writer, for one, was glad he had not been unkind. The strain of the descent and the long walk back to Castleton proved too much for the old man’s feeble frame, and brought on an illness, which proved to be a prelude to his decease.

The incident of the stone was the last excitement of the evening; and a couple of hours later every member of the party had regained the surface, tired in body but contented in mind.

Whether further discoveries of importance will be made with reference to the cavern it is hard to say. There appears to be little doubt that there is some relation between Eldon Hole and the Castleton caves, but whether such a communication will ever be established is a matter of conjecture. The writer is, however, informed that a party of explorers, not connected with the Pennine Club, has made progress below the level of the sandy beach.

If a through route could be established with either the Speedwell Cavern or the Peak, the achievement would rank as one of the most important in the history of the district; but it is hoped that the clothes of the explorers will not be burnt from off their backs like the feathers of the goose which came in contact with the purgatorial fires.